×

Regen VS Series

Series Motor

The series motor provides high starting torque and is able to move very large shaft loads when it is first

energized. Figure 12-10 shows the wiring diagram of a series motor. From the diagram you can see that the

field winding in this motor is wired in series with the armature winding. This is the attribute that gives

the series motor its name.

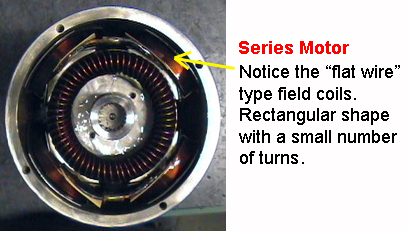

Since the series field winding is connected in series with the armature, it will carry the same amount of

current that passes through the armature. For this reason the field is made from heavy-gauge wire that is

large enough to carry the load. Since the wire gauge is so large, the winding will have only a few turns of

wire. In some larger DC motors, the field winding is made from copper bar stock rather than the conventional

round wire used for power distribution. The square or rectangular shape of the copper bar stock makes it fit

more easily around the field pole pieces. It can also radiate more easily the heat that has built up in the

winding due to the large amount of current being carried.

FIGURE 12-10 Electrical diagram of series motor. Notice that the series field is identified as S1 and S2.

The amount of current that passes through the winding determines the amount of torque the motor shaft can

produce. Since the series field is made of large conductors, it can carry large amounts of current and

produce large torques. For example, the starter motor that is used to start an automobile's engine is a

series motor and it may draw up to 500 A when it is turning the engine's crankshaft on a cold morning.

Series motors used to power hoists or cranes may draw currents of thousands of amperes during operation.

The series motor can safely handle large currents since the motor does not operate for an extended period. In

most applications the motor will operate for only a few seconds while this large current is present. Think

about how long the starter motor on the automobile must operate to get the engine to start. This period is

similar to that of industrial series motors.

Series Motor Operation

Operation of the series motor is easy to understand. In Fig. 12-10 you can see that the field winding is

connected in series with the armature winding. This means that power will be applied to one end of the

series field winding and to one end of the armature winding (connected at the brush).

When voltage is applied, current begins to flow from negative power supply terminals through the series

winding and armature winding. The armature is not rotating when voltage is first applied, and the only

resistance in this circuit will be provided by the large conductors used in the armature and field windings.

Since these conductors are so large, they will have a small amount of resistance. This causes the motor to

draw a large amount of current from the power supply. When the large current begins to flow through the

field and armature windings, it causes a strong magnetic field to be built. Since the current is so large,

it will cause the coils to reach saturation, which will produce the strongest magnetic field possible.

Producing Back EMF

The strength of these magnetic fields provides the armature shafts with the greatest amount of torque

possible. The large torque causes the armature to begin to spin with the maximum amount of power. When the

armature begins to rotate, it begins to produce voltage. This concept is difficult for some students to

understand since the armature is part of the motor at this time.

You should remember from the basic theories of magnetism that anytime a magnetic field passes a coil of wire,

a current will be produced. The stronger the magnetic field is or the faster the coil passes the flux lines,

the more current will be generated. When the armature begins to rotate, it will produce a voltage that is of

opposite polarity to that of the power supply. This voltage is called back voltage, back EMF (electromotive

force), or counter EMF. The overall effect of this voltage is that it will be subtracted from the supply

voltage so that the motor windings will see a smaller voltage potential.

When Ohm's law is applied to this circuit, you will see that when the voltage is slightly reduced, the

current will also be reduced slightly. This means that the series motor will see less current as its speed

is increased. The reduced current will mean that the motor will continue to lose torque as the motor speed

increases. Since the load is moving when the armature begins to pick up speed, the application will require

less torque to keep the load moving. This works to the motor's advantage by automatically reducing the motor

current as soon as the load begins to move. It also allows the motor to operate with less heat buildup.

This condition can cause problems if the series motor ever loses its load. The load could be lost when a

shaft breaks or if a drive pin is sheared. When this occurs, the load current is allowed to fall to a

minimum, which reduces the amount of back EMF that the armature is producing. Since the armature is not

producing a sufficient amount of back EMF and the load is no longer causing a drag on the shaft, the

armature will begin to rotate faster and faster. It will continue to increase rotational speed until it is

operating at a very high speed. When the armature is operating at high speed, the heavy armature windings

will be pulled out of their slots by centrifugal force. When the windings are pulled loose, they will catch

on a field winding pole piece and the motor will be severely damaged. This condition is called runaway and

you can see why a DC series motor must have some type of runaway protection. A centrifugal switch can be

connected to the motor to de-energize the motor starter coil if the rpm exceeds the set amount. Other

sensors can be used to de-energize the circuit if the motor's current drops while full voltage is applied to

the motor. The most important part to remember about a series motor is that it is difficult to control its

speed by external means because its rpm is determined by the size of its load. (In some smaller series

motors, the speed can be controlled by placing a rheostat in series with the supply voltage to provide some

amount of change in resistance to control the voltage to the motor.)

Figure 12-11 shows the relationship between series motor speed and armature current. From this curve you can

see that when current is low (at the top left), the motor speed is maximum, and when current increases, the

motor speed slows down (bottom right). You can also see from this curve that a DC motor will run away if the

load current is reduced to zero. (It should be noted that in larger series machines used in industry, the

amount of friction losses will limit the highest speed somewhat.)

FIGURE 12-11 The relationship between series motor speed and the armature current.

Reversing the Rotation

The direction of rotation of a series motor can be changed by changing the polarity of either the armature or

field winding. It is important to remember that if you simply changed the polarity of the applied voltage,

you would be changing the polarity of both field and armature windings and the motor's rotation would remain

the same.

FIGURE 12-12 DC series motor connected to forward and reverse motor starter.

Since only one of the windings needs to be reversed, the armature winding is typically used because its

terminals are readily accessible at the brush rigging. Remember that the armature receives its current

through the brushes, so that if their polarity is changed, the armature's polarity will also be changed. A

reversing motor starter is used to change wiring to cause the direction of the motor's rotation to change by

changing the polarity of the armature windings. Figure 12-12 shows a DC series motor that is connected to a

re-versing motor starter. In this diagram the armature's terminals are marked Al and A2 and the field

terminals are marked Sl and S2.

When the forward motor starter is energized, the top contact identified as F closes so the Al terminal is

connected to the positive terminal of the power supply and the bottom F contact closes and connects

terminals A2 and Sl. Terminal S2 is connected to the negative terminal of the power supply. When the reverse

motor starter is energized, terminals Al and A2 are reversed. A2 is now connected to the positive terminal.

Notice that S2 remains connected to the negative terminal of the power supply terminal. This ensures that

only the armature's polarity has been changed and the motor will begin to rotate in the opposite direction.

You will also notice the normally closed (NC) set of R contacts connected in series with the forward push

button, and the NC set of F contacts connected in series with the reverse push button. These contacts

provide an interlock that prevents the motor from being changed from forward to reverse direction without

stopping the motor. The circuit can be explained as follows: when the forward push button is depressed,

current will flow from the stop push button through the NC R interlock contacts, and through the forward

push button to the forward motor starter (FMS) coil. When the FMS coil is energized, it will open its NC

contacts that are connected in series with the reverse push button. This means that if someone depresses the

reverse push button, current could not flow to the reverse motor starter (RMS) coil. If the person

depressing the push buttons wants to reverse the direction of the rotation of the motor, he or she will need

to depress the stop push button first to de-energize the FMS coil, which will allow the NC F contacts to

return to their NC position. You can see that when the RMS coil is energized, its NC R contacts that are

connected in series with the forward push button will open and prevent the current flow to the FMS coil if

the forward push button is depressed. You will see a number of other ways to control the FMS and RMS starter

in later discussions and in the chapter on motor controls.

Installing and Troubleshooting

Since a series motor has only two leads brought out of the motor for installation wiring, this wiring can be

accomplished rather easily. If the motor is wired to operate in only one direction, the motor terminals can

be connected to a manual or magnetic starter. If the motor's rotation is required to be reversed

periodically, it should be connected to a reversing starter.

Most DC series motors are used in direct-drive applications. This means that the load is connected directly

to the armature's shaft. This type of load is generally used to get the most torque converted. Belt-drive

applications are not recommended since a broken belt would allow the motor to run away. After the motor has

been installed, a test run should be used to check it out. If any problems occur, the troubleshooting

procedures should be used.

The most likely problem that will occur with the series motor is that it will develop an open in one of its

windings or between the brushes and the commutator. Since the coils in a series motor are connected in

series, each coil must be functioning properly or the motor will not draw any current. When this occurs, the

motor cannot build a magnetic field and the armature will not turn. Another problem that is likely to occur

with the motor circuit is that circuit voltage will be lost due to a blown fuse or circuit breaker. The

motor will respond similarly in both of these conditions.

The best way to test a series motor is with a voltmeter. The first test should be for applied voltage at the

motor terminals. Since the motor terminals are usually connected to a motor starter, the test leads can be

placed on these terminals. If the meter shows that full voltage is applied, the problem will be in the

motor. If it shows that no voltage is present, you should test the supply voltage and the control circuit to

ensure that the motor starter is closed. If the motor starter has a visual indicator, be sure to check to

see that the starter's contacts are closed. If the overloads have tripped, you can assume that they have

sensed a problem with the motor or its load. When you reset the overloads, the motor will probably start

again but remember to test the motor thoroughly for problems that would cause an overcurrent situation.

If the voltage test indicates that the motor has full applied voltage to its terminals but the motor is not

operating, you can assume that you have an open in one of the windings or between the brushes and the

armature and continue testing. Each of these sections should be disconnected from each other and voltage

should be removed so that they can be tested with an ohmmeter for an open. The series field coils can be

tested by putting the ohmmeter leads on terminals Sl and S2. If the meter indicates that an open exists, the

motor will need to be removed and sent to be rewound or replaced. If the meter indicates that the field coil

has continuity, you should continue the procedure by testing the armature.

The armature can also be tested with an ohmmeter by placing the leads on the terminals marked Al and A2. If

the meter shows continuity, rotate the armature shaft slightly to look for bad spots where the commutator

may have an open or the brushes may not be seated properly. If the armature test indicates that an open

exists, you should continue the test by visually inspecting the brushes and commutator. You may also have an

open in the armature coils. The armature must be removed from the motor frame to be tested further. When you

have located the problem, you should remember that the commutator can be removed from the motor while the

motor remains in place and it can be turned down on a lathe. When the commutator is replaced in the motor,

new brushes can be installed and the motor will be ready for use.

It is possible that the motor will develop a problem but still run. This type of problem usually involves the

motor overheating or not being able to pull its rated load. This type of problem is different from an open

circuit because the motor is drawing current and trying to run. Since the motor is drawing current, you must

assume that there is not an open circuit. It is still possible to have brush problems that would require the

brushes to be re-seated or replaced. Other conditions that will cause the motor to overheat include loose or

damaged field and armature coils. The motor will also overheat if the armature shaft bearing is in need of

lubrication or is damaged. The bearing will seize on the shaft and cause the motor to build up friction and

overheat.

If either of these conditions occurs, the motor may be fixed on site or be removed for extensive repairs.

When the motor is restarted after repairs have been made, it is important to monitor the current usage and

heat buildup. Remember that the motor will draw DC current so that an AC clamp-on ammeter will not be useful

for measuring the DC current. You will need to use an ammeter that is specially designed for very large DC

currents. It is also important to remember that the motor can draw very high locked-rotor current when it is

starting, so the ammeter should be capable of measuring currents up to 1000 A. After the motor has completed

its test run successfully, it can be put back into operation for normal duty. Anytime the motor is suspected

of faulty operation, the troubleshooting procedure should be rechecked.

DC Series Motor Used as a Universal Motor

The series motor is used in a wide variety of power tools such as electric hand drills, saws, and power

screwdrivers. In most of these cases, the power source for the motor is AC voltage. The DC series motor will

operate on AC voltage. If the motor is used in a hand drill that needs variable-speed control, a field

rheostat or other type of current control is used to control the speed of the motor. In some newer tools,

the current control uses solid-state components to control the speed of the motor. You will notice that the

motors used for these types of power tools have brushes and a commutator, and these are the main parts of

the motor to wear out. You can use the same theory of operation provided for the DC motor to troubleshoot

these types of motors.

Shunt or Regen or SEPEX Motor

The shunt motor is different from the series motor in that the field winding is connected in parallel with

the armature instead of in series. You should remember from basic electrical theory that a parallel circuit

is often referred to as a shunt. Since the field winding is placed in parallel with the armature, it is

called a shunt winding and the motor is called a shunt motor. Figure 12-13 shows a diagram of a shunt motor.

Notice that the field terminals are marked Fl and F2, and the armature terminals are marked Al andA2. You

should notice in this diagram that the shunt field is represented with multiple turns using a thin line.

FIGURE 12-13 Diagram of DC shunt motor. Notice the shunt coil is identified as a coil of fine wire with many

turns that is connected in parallel (shunt) with the armature.

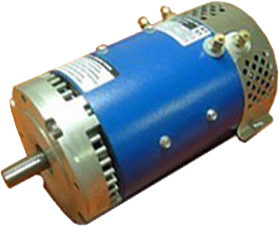

FIGURE 12-14 Typical DC shunt motor. These motors are available in a variety of sizes. This motor is a 1 hp

(approximately 8 in. tall).

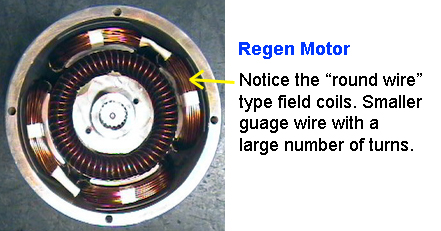

The shunt winding is made of small-gauge wire with many turns on the coil. Since the wire is so small, the

coil can have thousands of turns and still fit in the slots. The small-gauge wire cannot handle as much

current as the heavy-gauge wire in the series field, but since this coil has many more turns of wire, it can

still produce a very strong magnetic field. Figure 12-14 shows a picture of a DC shunt motor.

Shunt Motor Operation

A shunt motor has slightly different operating characteristics than a series motor. Since the shunt field

coil is made of fine wire, it cannot produce the large current for starting like the series field. This

means that the shunt motor has very low starting torque, which requires that the shaft load be rather small.

When voltage is applied to the motor, the high resistance of the shunt coil keeps the overall current flow

low. The armature for the shunt motor is similar to the series motor and it will draw current to produce a

magnetic field strong enough to cause the armature shaft and load to start turning. Like the series motor,

when the armature begins to turn, it will produce back EMF. The back EMF will cause the current in the

armature to begin to diminish to a very small level. The amount of current the armature will draw is

directly related to the size of the load when the motor reaches full speed. Since the load is generally

small, the armature current will be small. When the motor reaches full rpm, its speed will remain fairly

constant.

Controlling the Speed

When the shunt motor reaches full rpm, its speed will remain fairly constant. The reason the speed remains

constant is due to the load characteristics of the armature and shunt coil. You should remember that the

speed of a series motor could not be controlled since it was totally dependent on the size of the load in

comparison to the size of the motor. If the load was very large for the motor size, the speed of the

armature would be very slow. If the load was light compared to the motor, the armature shaft speed would be

much faster, and if no load was present on the shaft, the motor could run away.

The shunt motor's speed can be controlled. The ability of the motor to maintain a set rpm at high speed when

the load changes is due to the characteristic of the shunt field and armature. Since the armature begins to

produce back EMF as soon as it starts to rotate, it will use the back EMF to maintain its rpm at high speed.

If the load increases slightly and causes the armature shaft to slow down, less back EMF will be produced.

This will allow the difference between the back EMF and applied voltage to become larger, which will cause

more current to flow. The extra current provides the motor with the extra torque required to regain its rpm

when this load is increased slightly.

The shunt motor's speed can be varied in two different ways. These include varying the amount of current

supplied to the shunt field and controlling the amount of current supplied to the armature. Controlling the

current to the shunt field allows the rpm to be changed 10-20% when the motor is at full rpm.

This type of speed control regulation is accomplished by slightly increasing or decreasing the voltage

applied to the field. The armature continues to have full voltage applied to it while the current to the

shunt field is regulated by a rheostat that is connected in series with the shunt field. When the shunt

field's current is decreased, the motor's rpm will increase slightly. When the shunt field's current is

reduced, the armature must rotate faster to produce the same amount of back EMF to keep the load turning. If

the shunt field current is increased slightly, the armature can rotate at a slower rpm and maintain the

amount of back EMF to produce the armature current to drive the load. The field current can be adjusted with

a field rheostat or an SCR current control.

The shunt motor's rpm can also be controlled by regulating the voltage that is applied to the motor armature.

This means that if the motor is operated on less voltage than is shown on its data plate rating, it will run

at less than full rpm. You must remember that the shunt motor's efficiency will drop off drastically when it

is operated below its rated voltage. The motor will tend to overheat when it is operated below full voltage,

so motor ventilation must be provided. You should also be aware that the motor's torque is reduced when it

is operated below the full voltage level.

Since the armature draws more current than the shunt field, the control resistors were much larger than those

used for the field rheostat. During the 1950s and 1960s SCRs were used for this type of current control. The

SCR was able to control the armature current since it was capable of controlling several hundred amperes. In

Chapter 11 we provided an in-depth explanation of the DC motor drive.

Torque Characteristics

The armature's torque increases as the motor gains speed due to the fact that the shunt motor's torque is

directly proportional to the armature current. When the motor is starting and speed is very low, the motor

has very little torque. After the motor reaches full rpm, its torque is at its fullest potential. In fact,

if the shunt field current is reduced slightly when the motor is at full rpm, the rpm will increase slightly

and the motor's torque will also in-crease slightly. This type of automatic control makes the shunt motor a

good choice for applications where constant speed is required, even though the torque will vary slightly due

to changes in the load. Figure 12-15 shows the torque/speed curve for the shunt motor. From this diagram you

can see that the speed of the shunt motor stays fairly constant throughout its load range and drops slightly

when it is drawing the largest current.

FIGURE 12-15 A curve that shows the armature current versus the armature speed for a shunt motor. Notice that

the speed of a shunt motor is nearly constant.

FIGURE 12-16 Diagram of a shunt motor connected to a reversing motor starter. Notice that the shunt field is

connected across the armature and it is not reversed when the armature is reversed.

Reversing the Rotation

The direction of rotation of a DC shunt motor can be reversed by changing the polarity of either the armature

coil or the field coil. In this application the armature coil is usually changed, as was the case with the

series motor. Figure 12-16 shows the electrical diagram of a DC shunt motor connected to a forward and

reversing motor starter. You should notice that the Fl and F2 terminals of the shunt field are connected

directly to the power supply, and the Al and A2 terminals of the armature winding are connected to the

reversing starter.

When the FMS is energized, its contacts connect the Al lead to the positive power supply terminal and the A2

lead to the negative power supply terminal. The Fl motor lead is connected directly to the positive terminal

of the power supply and the F2 lead is connected to the negative terminal. When the motor is wired in this

configuration, it will begin to run in the forward direction.

When the RMS is energized, its contacts reverse the armature wires so that the Al lead is connected to the

negative power supply terminal and the A2 lead is connected to the positive power supply terminal. The field

leads are connected directly to the power supply, so their polarity is not changed. Since the field's

polarity has remained the same and the armature's polarity has reversed, the motor will begin to rotate in

the reverse direction. The control part of the diagram shows that when the FMS coil is energized, the RMS

coil is locked out.

Installing a Shunt motor

A shunt motor can be installed easily. The motor is generally used in belt-drive applications. This means

that the installation procedure should be broken into two sections, which include the mechanical

installation of the motor and its load, and the installation of electrical wiring and controls.

When the mechanical part of the installation is completed, the alignment of the motor shaft and the load

shaft should be checked. If the alignment is not true, the load will cause an undue stress on the armature

bearing and there is the possibility of the load vibrating and causing damage to it and the motor. After the

alignment is checked, the tension on the belt should also be tested. As a rule of thumb, you should have

about V2 to 1/4 inch of play in the belt when it is properly tensioned.

Several tension measurement devices are available to determine when a belt is tensioned properly. The belt

tension can also be compared to the amount of current the motor draws. The motor must have its electrical

installation completed to use this method.

The motor should be started, and if it is drawing too much current, the belt should be loosened slightly but

not enough to allow the load to slip. If the belt is slipping, it can be tightened to the point where the

motor is able to start successfully and not draw current over its rating.

The electrical installation can be completed before, after, or during the mechanical installation. The first

step in this procedure is to locate the field and armature leads in the motor and prepare them for field

connections. If the motor is connected to magnetic or manual across the line starter, the Fl field coil wire

can be connected to the Al armature lead and an interconnecting wire, which will be used to connect these

leads to the Tl terminal on the motor starter. The F2 lead can be connected to the A2 lead and a second

wire, which will connect these leads to the T2 motor starter terminal.

When these connections are completed, field and armature leads should be replaced back into the motor and the

field wiring cover or motor access plate should be replaced. Next the DC power supply's positive and

negative leads should be connected to the motor starter's LI and L2 terminals, respectively.

After all of the load wires are connected, any pilot devices or control circuitry should be installed and

connected. The control circuit should be tested with the load voltage disconnected from the motor. If the

control circuit uses the same power source as the motor, the load circuit can be isolated so the motor will

not try to start by disconnecting the wire at terminal L2 on the motor starter. Operate the control circuit

several times to ensure that it is wired correctly and operating properly. After you have tested the control

circuit, the lead can be replaced to the L2 terminal of the motor starter and the motor can be started and

tested for proper operation. Be sure to check the motor's voltage and current while it is under load to

ensure that it is operating correctly. It is also important to check the motor's temperature periodically

until you are satisfied the motor is operating correctly.

If the motor is connected to a reversing starter or reduced-voltage starting circuit, their operation should

also be tested. You may need to read the material in Section 15.3.6 to fully understand the operation of

these methods of starting the motor using reduced-voltage methods. If the motor is not operating correctly

or develops a fault, a troubleshooting procedure should be used to test the motor and locate the problem.

Troubleshooting

When a DC shunt motor develops a fault, you must be able to locate the problem quickly and return the motor

to service or have it replaced. The most likely problems to occur with the shunt motor include loss of

supply voltage or an open in either the shunt winding or the armature winding. Other problems may arise that

cause the motor to run abnormally hot even though it continues to drive the load. The motor will show

different symptoms for each of these problems, which will make the troubleshooting procedure easier.

When you are called to troubleshoot the shunt motor, it is important to determine if the problem occurs while

the motor is running or when it is trying to start. If the motor will not start, you should listen to see if

the motor is humming and trying to start. When the supply voltage has been interrupted due to a blown fuse

or a de-energized control circuit, the motor will not be able to draw any current and it will be silent when

you try to start it. You can also determine that the supply voltage has been lost by measuring it with a

voltmeter at the starter's LI and L2 terminals. If no voltage is present at the load terminals, you should

check for voltage at the starter's Tl and T2 terminals. If voltage is present here but not at the load

terminals, it indicates that the motor starter is de-energized or defective. If no voltage is present at the

Tl and T2 terminals, it indicates that supply voltage has been lost prior to the motor starter. You will

need to check the supply fuses and the rest of the supply circuit to locate the fault.

If the motor tries to start and hums loudly, it indicates that the supply voltage is present. The problem in

this case is probably due to an open field winding or armature winding. It could also be caused by the

supply voltage being too low.

The most likely problem will be an open in the field winding since it is made from small-gauge wire. The open

can occur if the field winding draws too much current or develops a short circuit between the insulation in

the coils. The best way to test the field is to remove supply voltage to the motor by opening the disconnect

or de-energizing the motor starter. Be sure to use a lockout when you are working on the motor after the

disconnect has been opened. The lockout is a device that is placed on the handle of the disconnect after the

handle is placed in the off position, and it allows a padlock to be placed around it so it cannot be removed

until the technician has completed the work on the circuit. If lockout has extra holes, additional padlocks

can be placed on it by other technicians who are also working on this system. This ensures that the power

cannot be returned to the system until all technicians have removed their padlocks. The lockout will be

explained in detail in the chapter on motor controls later in this text.

After power has been removed, the field terminals should be isolated from the armature coil. This can be

accomplished by disconnecting one set of leads where the field and armature are connected together. Remember

that the field and armature are connected in parallel and if they are not isolated, your continuity test

will show a completed circuit even if one of the two windings has an open.

When you have the field coil isolated from the armature coil, you can proceed with the continuity test. Be

sure to use the R X 1k or R X 10k setting on the ohmmeter because the resistance in the field coil will be

very high since the field coil may be wound from several thousand feet of wire. If the field winding test

indicates the field winding is good, you should continue the procedure and test the armature winding for

continuity.

The armature winding test may show that an open has developed from the coil burning open or from a problem

with the brushes. Since the brushes may be part of the fault, they should be visually inspected and replaced

if they are worn or not seating properly. If the commutator is also damaged, the armature should be removed,

so the commutator can be turned down on a lathe.

If either the field winding or the armature winding has developed an open circuit, the motor will have to be

removed and replaced. In some larger motors it will be possible to change the armature by itself rather than

remove and replace the entire motor. If the motor operates but draws excessive current or heats up, the

motor should be tested for loose or shorting coils. Field coils may tend to come loose and cause the motor

to vibrate and overheat, or the armature coils may come loose from their slots and cause problems. If the

motor continues to overheat or operate roughly, the motor should be removed and sent to a motor rebuilding

shop so that a more in-depth test may be performed to find the problem before the motor is permanently

damaged by the heat.